Gearóid Ó Loingsigh 02 November 2023

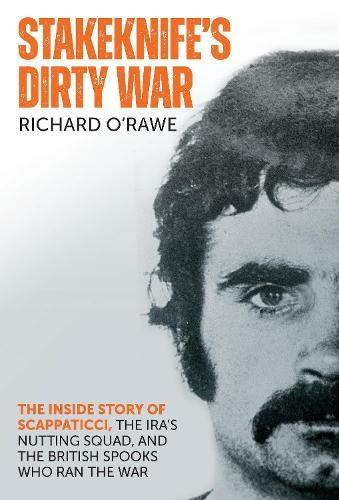

Richard O’ Rawe’s Stakeknife’s Dirty War is a timely book, coming as it does after the death, or supposed death of Stakeknife in England and what looks like a thwarting of the intent and findings of Boutcher’s Kenova Inquiry into the affair.

It is now accepted by all that IRA Volunteer Scappaticci was also the British agent known as Stakeknife.

O’Rawe had access to IRA volunteers and former intelligence operatives and weaves together aspects of Scappaticci’s life and role into a narrative that is convincing and despite the nature of the subject matter, torture, murder and betrayal it is an easy read.

O’Rawe also introduces us to Scappaticci the person. The person however, isn’t any more likeable than the British agent, torturer and murderer. In fact, it would seem they are flip sides of the same coin. Scappaticci was an industrious character, always on the make, running private tax scams.

He was used to money long before he became a paid British agent. His fortune earned from murders on behalf of the British and the IRA, though the IRA weren’t giving him anything like the sum the British did, is estimated to be in the region of a million pounds in pay-outs.

He also had various properties. Scappaticci was also a lowlife thug long before the British and the IRA gave him carte blanche to murder and torture his way through republican ranks. Some of things he did, had he not been in the IRA would have led to him being kneecapped by the IRA.

A man called Collins made the mistake of publicly calling the area in Twinbrook in which Scappaticci lived ‘Provie Corner’. Scappaticci did not like that and decided that Collins had to pay for his transgression.

He knocked on Collins’ door and, when it was answered, the informer battered the older man multiple times over the head with a sock containing a brick. Only when Collins collapsed did Scappaticci walk away.

This is the type of low life thuggish behaviour that the IRA was willing to tolerate and perhaps even encourage from people like Scappaticci. In a genuinely political movement, a thug like Scappaticci would have been out on his ear. But not in the IRA nor in Sinn Féin.

He was, to paraphrase the Yanks when talking about the Nicaraguan dictator Somoza, “he may be a son of a bitch, but he is our son of a bitch”, though in this case it would seem that not only was he theirs he had just the qualities that both the IRA and the British valued, ruthless thuggish qualities.

Scappaticci the person and agent are intimately related it would seem though O’Rawe doesn’t explicitly say so. He does however, give us ample material with which to draw that conclusion.

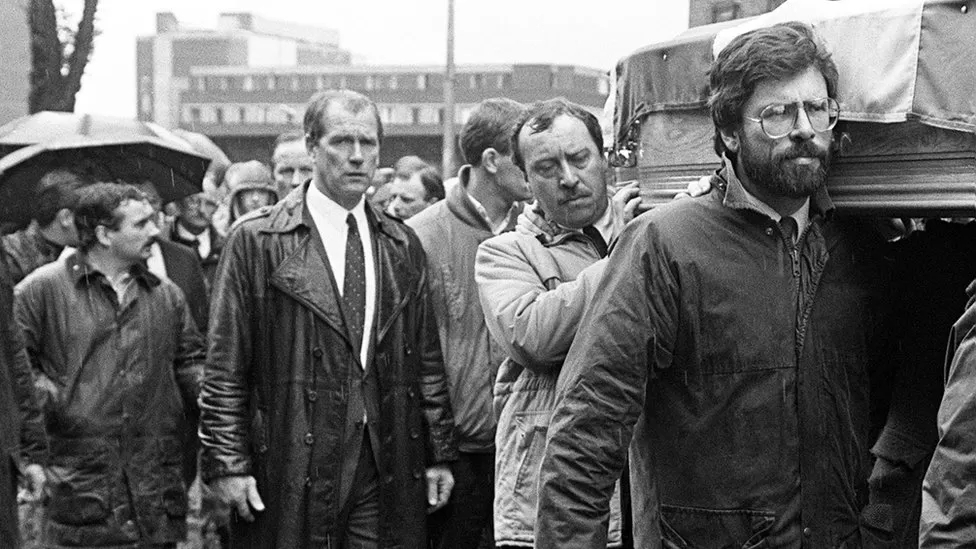

One of the issues never dealt with it in the press and not really fully covered here is what type of organisation recruits, tolerates and promotes such people. He was a reprobate who should never have graced the ranks of the IRA. That he did so, is down to Adams and co.

That is also clear from the book. It is not an aspersion on Adams or on McGuinness either to question their role.

The latter of the two comes in for some questioning in the book regarding his role and O’Rawe goes into some detail and also explains in the epilogue that before beginning his research he was unaware of the level of unease amongst republicans about McGuinness’ trustworthiness.

Though he does point out earlier that if McGuinness was a tout, why was it necessary for the British to have a spy such as Willie Carlin get close to him. The same could also be said of Adams.

The British had an agent, Denis Donaldson, whispering sweet nothings in Adam’s ear over many years, shaping Adam’s view of the world and reporting back to the British how successful he had been in his endeavours.

The Peace Process, in that regard, was partially the result of what ideas the British planted in Adam’s and McGuinness’ minds through their various agents. However, it does seem unlikely either of them were touts in the classical sense of the word.

They didn’t need to be, they were at a different level. They were both on the same side as Scappaticci in winding down the war, they just had different methods of going about it.

It is possible that at some stage they had dealings with the British security services in pursuit of common aims. O’ Rawe is not the first to question McGuinness either.

Ed Moloney has put forward the idea that the reprehensible proxy bombs that provoked so much revulsion were signed off on, precisely because they would strengthen the hands of those who sought to wind up the war.

O’Rawe gives many examples of what Scappaticci and the other British agents in the Internal Security Unit did. It wasn’t limited to executing alleged informers or those the British thought should be removed for various reasons under the guise of them being informers.

They were also in a position to give information on operations which led to the British either arresting or killing the Volunteers involved. The book opens with an account of one such operation, where fortunately they were able to pull back from it without the planned British ambush going ahead.

There were of course other incidents, one of them being Loughall where the British ambushed an entire unit of the IRA. Scappaticci and his ilk did great harm to the IRA, but they were not the reason the IRA lost the war, and O’Rawe doesn’t argue it was either.

However, others have made this point. But the IRA was never going to win the war, they weren’t going to outgun the Brits ever.

Another part of the problem of course, is related to Scappaticci. A movement so highly infiltrated would always have problems, but it is telling of the political weakness of the IRA and Sinn Féin that a thug like Scappaticci could rise through the ranks and remain at the top for so long.

That says more about their weaknesses, than anything else.

That Denis Donaldson, a British agent was the chief advisor to the IRA and Sinn Féin on strategy, for so long, shaping policy, whilst Scappaticci weeded out of the ranks anyone who would oppose it, says more about the weakness of republican politics than whether operations went ahead or not.

O’Rawe, however, is more interested in what happened and who bears responsibility for it.

He is quite clear that the IRA are to blame and is equally clear that those in the intelligence services who allowed Scappaticci and other British agents in the ISU to murder their way through republican ranks are also to blame.

He is not wrong in that, Danny Morrison described Scappaticci as Number 10’s murderer(1) and that he was, he was also the IRA and Sinn Féin’s murderer.

Adam’s infamously justified in a blasé fashion the IRA murder of alleged informer Charles McIlmurray in 1987 when he said that “like anyone else living in West Belfast [he] knows the consequence for informing is death.”(2)

Neither the British, the IRA, Sinn Féin and Gerry Adams in particular, get to wash their hands of the affair.

This book is an important contribution to uncovering the truth of Troubles, one which will neither please Sinn Féin nor the British and Irish governments written from the perspective of a former IRA volunteer.

It deserves to be read and kept on the book shelf as the issue is not going away any time soon.

end.

Notes

(1) Morrison, D. (30/01/2016) No 10’s Murderer – Scap https://www.dannymorrison.com/the-times-of-no-10s-main-murderer/

(2) See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Kwrj6Ku9ZU