Diarmuid Breatnach

(Reading time main text: 5 mins.)

On a wet Tuesday night in the large lobby of Windmill Lane Recording Studios, local community representatives met with representatives of political parties, Dublin City Council and the Gardaí to press for their community’s needs to be met.

The meeting on 24th October 2023 was convened by the City Quay Committee and its organiser, Patrick (“Paddy”) Bray raised concerns about the unmet needs of the local communities currently and for following generations.

Apart from the City Quay Committee, also represented were representatives of housing areas Markievicz House and Conway House, along with volunteer-managed youth service Talk About Youth.

Also in attendance were representation from political parties Fianna Fáil, Labour and Sinn Féin, all of which have TDs (members of Irish parliament) elected in the area. Dublin City Council was represented as the local municipal authority and Pearse Street as the nearest Garda station.

Presumably the presence of a Garda representative was in relation to discussion around a recent period of violent confrontations between opposing gangs of youth on the Samuel Beckett Bridge (but also Sean O’Casey Bridge) connecting South and North Liffey docklands.

It was striking that nearly all the community representatives were female, while most of the political representatives and each of DCC and the Gardaí were of male gender.

Paddy Bray opened the meeting outlining the local concerns about the area’s youth and the lack of constructive activities for them, the local youth service being underfunded, under-staffed and with no permanent base.

Bray went on to outline a dire absence of any kind of community facility for the local community, while property development went on around them, including four hotels in recent times, with no sites designated for affordable housing or community needs.

Other community representatives also pressed their needs hard and raised issues of applications for building on existing sites without consideration of the community’s needs in housing, parking, child and young person development, mental health or green space.

A number raised concerns about rat infestation in a housing area, emanating from a derelict site, followed by some discussion about where responsibility lay to address the problem as the site is in private ownership (though there was a suggestion of an enforceable abatement order).

The responses of the political party representatives and the Dublin City Council Area 2 officer were generally supportive, though a disagreement did emerge as to whether the City Council were doing enough to control the rat infestation.

Evoking a medieval or early 1900s scenario, a community representative reported that a man visited their housing area on a voluntary basis to kill rats and at a recent visit, had killed seven. Photos of live and dead rats on a phone were handed around (to shudders from some of the men).

The meeting concluded with an agreement to form a campaigning committee for the resources and sites needed, for the political representatives to support its aims and for the Area 2 DCC Manager to report back to his own management.

Paddy Bray asked all present to spread the word among their contacts to enlist further support.

THE COMMUNITY: LOSS, NEEDS AND HISTORY

The name of the building in which the meeting was held is famous in Irish recording events though most probably associate it in particular with the previous recording studio on the site and the rock group U2.

A plan for a six-storey block on the site was defeated by local protests in 2008 but the original studios were demolished with the exception of the U2 fans’ graffiti wall, which was later sold and proceeds donated to a charity fundraising for awareness of men’s health and treatment needs.

The new building is owned by the formerly investment trust company, now Hibernia property development company which, despite the name, as is now common in Ireland, is owned by a foreign corporation.1

Property speculators plan to demolish the City Arts Centre, a resource for the community but derelict and empty for two decades on Moss Street on the South docks, in order to build a 24-storey office block.

Unusually perhaps, the demolition application is being opposed by Dublin City Council2 which has appealed it to an Bord Pleanála3 and the speculator has taken the case to court.

As mentioned in the meeting, an existing facility for the community, the Markievicz swimming pool, despite 1,600 signatures to save it, is to close for the construction of a station for the projected underground Metrolink, another infrastructure planned for private or part-private ownership.4

As one of the community representatives commented, there is already a train station nearby; not only that but the tracks of that station are several storeys above ground, making an underground connection with Metrolink quite feasible.

The swimming pool facilities are now to be located at a site 3 km away in Ringsend, a housing district at the end of the docks and partly on the seafront, which has football pitches and green space very close nearby. 5

It is indeed late in the day as indicated by the huge property development on the South Quays but the communities are getting organised as can be seen from this meeting, a commemoration of a fatal 1960s housing collapse and protests about local church neglect by the Diocese.6

Some may think it is too late or that the speculative property and financial forces ranged against them, with their multiple political and other connections, are too strong. But their community’s needs now and for generations to come are powerful incentives for which to struggle too.

The south and north quays communities, neglected by the authorities and rode over roughshod in the past, with their remnants now under threat, are essentially working and lower-middle class communities which have never been given the resources they earned and deserved.

As in many other parts of Dublin, working class communities were ravaged by the heroin epidemic in the 1980s and regarded in the main by the authorities as a policing problem, with anti-drug campaigners ironically targeted more than drug lords.

In the course of that social crisis, many developments of physical and political nature took place which the working class was not well-placed to resist.

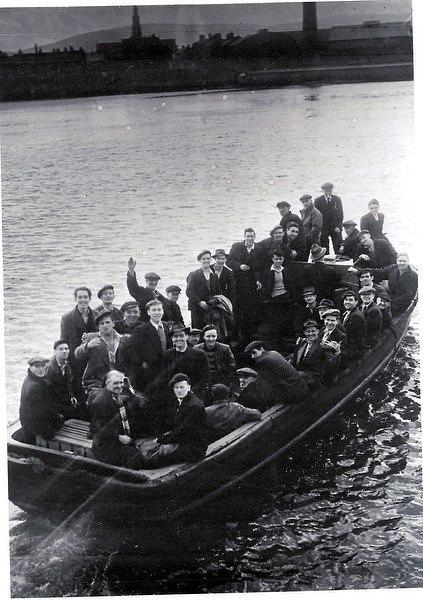

An outing on the old Liffey ferry boat, in regular use when there was no bridge crossing the Liffey eastward and downriver past Butt Bridge (Photo sourced: Dublin Dockers’ Preservation Society)

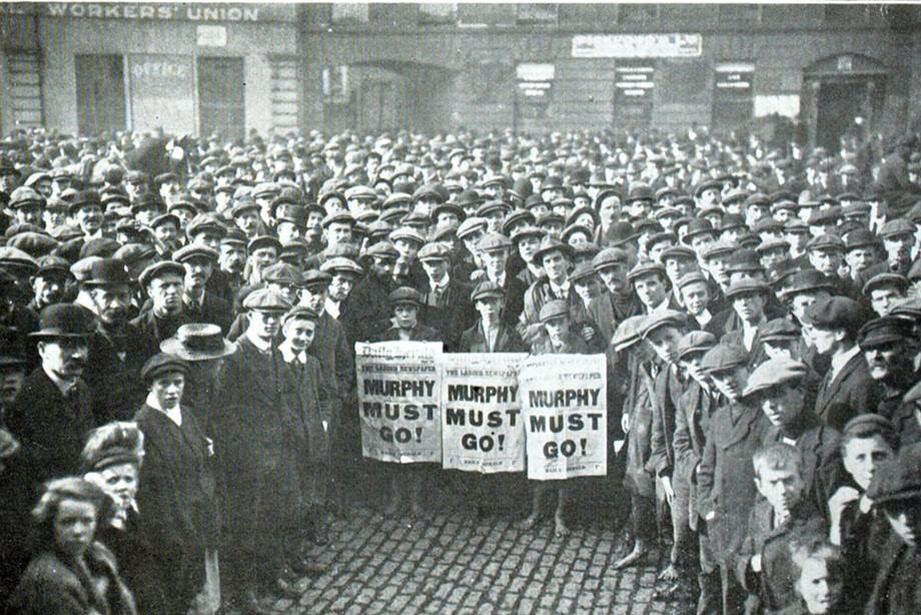

However, the people of the docklands were an important part of the working class movement in the early 1900s, winning many union battles against the employers until defeated by the latter’s alliance with police, magistrates, churches and media after eight months of struggle 1913-1914.

They rose out of that defeat and rebuilt their fighting organisations, including the first workers’ army in the world (and which recruited women, some of them appointed officers),7 fought again in the 1916 Rising and after that in Dockland areas during the War of Independence.

Indeed, during the 1916 Rising it is remarkable that despite British shelling from naval units in the Liffey, they did not attempt to land soldiers on any of the Dublin quays at that time, disembarking British reinforcements into Dun Laoghaire instead and marching 8 miles8 in from there.

If the working class of the south Dublin dockland is stirring it may still achieve more than many may expect.

End.

FOOTNOTES

1Purchased by Brookfield Asset Management, a Canadian company, in 2022

2https://www.breakingnews.ie/ireland/city-arts-centre-would-cost-e90000-to-get-to-satisfactory-condition-court-told-1488548.html

3Many applications agreed by DCC Planning Department have also been appealed to An Bord Pleanála and that organisation has been immersed in controversy over criminality in management and low staff morale leading to a high backlog of appeals awaiting judgements.

4https://www.irishtimes.com/business/2023/06/05/up-to-300m-spent-on-various-dublin-metro-projects-to-date/ for the Metrolink but also notably in the LUAS tram network and Transport for Ireland buses in Dublin with regard to public transport infrastructure but also to be seen in toll roads and in electronic communications infrastructures.

5One could form the suspicion that the ultimate plan is to move south docks working class facilities to Ringsend and Irish Town, with the communities themselves to follow or to fade away, leaving the whole area free for property speculators.

6The diocese protest was not reported on in Rebel Breeze but the housing collapse commemoration, at which the lack of local affordable housing was raised, was.

7The Irish Citizen Army, founded after calls by both James Connolly and Jim Larkin.

814 kilometres.

SOURCES

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Windmill_Lane_Studios

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hibernia_Real_Estate_Group

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MetroLink_(Dublin)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MetroLink_(Dublin)