Diarmuid Breatnach

(Reading time: 6 mins.)

In Dublin’s south docklands the property developers and the corporations dominate city planning and therefore the landscape. And the working class community there feel that they’re being squeezed out.

I’ve met with some concerned people from parts of this community in the past to report on their situation and concerns for Rebel Breeze and did so again recently.

YOUNG PEOPLE – education, training, socialising

“There’s nothing here for our young people” said one, expressing concern over the attraction for teenagers of physical confrontations with other teens from across the river which have taken place on the Samuel Beckett Bridge over the Liffey.

A young man training as an apprentice in engineering attends a mixed martial arts club but has to go miles away to another area to attend there. Between his industrial training, travel and athletic training he has little time to spare for socialising.

I comment that those sporting activities tend to concentrate on male youth and only some of those also but he tells me that nearly half the regular membership of his club is female. A community centre could provide space and time for such training but they say they have no such centre.

St. Andrew’s Hall is a community centre in the area and there are mixed opinions in the group about it but I know from my own enquiries that the available rooms are committed to weekly booked activities (and our meeting had to take place in a quiet corner of an hotel bar).

As a former youth worker and in voluntary centre management, I know that a community centre can serve all ages across the community, from parents and toddlers through youth clubs to sessions for adults and elders.

Discussing youth brings the talk into education and training. As discussed in a previous report of mine, the youth are not being trained in information technology, which is the employment offered in most of the corporations in “the glass cages that spring up along the quay.”1

“If they’re lucky, they’ll get work in the buildings as cleaners or serving lattes and snack in the new cafes”. Some opined that the corporations in the area should be providing their youth with the training while others thought Trinity College should be doing so.

HOUSING – price and air quality

Universal municipal housing in the area has declined due to privatisation of housing stock and refusal to build more. A former municipal block in Fenian Street, empty for years is now to be replaced but the “affordable” allocation has been progressively reduced, ending now at zero.

Property speculators (sorry, “developers”) with banker support are building office blocks and apartment blocks in the areas, the latter units priced beyond the range of most local people. The average rent for a two-bed apartment in the area is €2,385;2 to buy a 3-bedroom house €615,000.3

The Joyce House site and attached ground area could provide housing and a community centre but appears planned to go to speculators.

The Markievicz swimming pool near Tara Street has been closed and the local people are told they can go to Ringsend for swimming, an area which already has better community facilities than are available to the communities further west along docklands

A huge amount of traffic goes through the area and one person stated that Macken Street tested as having the worst air quality in Ireland. “I have to close my windows to keep out the noise and pollution,” said another; “the curtains would be black.”

‘They want us out’

If some town planner were intending to establish a community somewhere, s/he would plan for housing, obviously, so the people would have somewhere to live. But a proper plan would provide also for education and training, along with social facilities — and employment.

But if someone were intending instead to get rid of a community, s/he would target exactly the same elements, whittling them down or removing them altogether. This what some local people feel is intended for their community.

“We feel we’re not wanted here,” said one and others agreed, “They want us to move out.” “But we’re not going! We’re staying,” said another, to grim nodding of heads around.

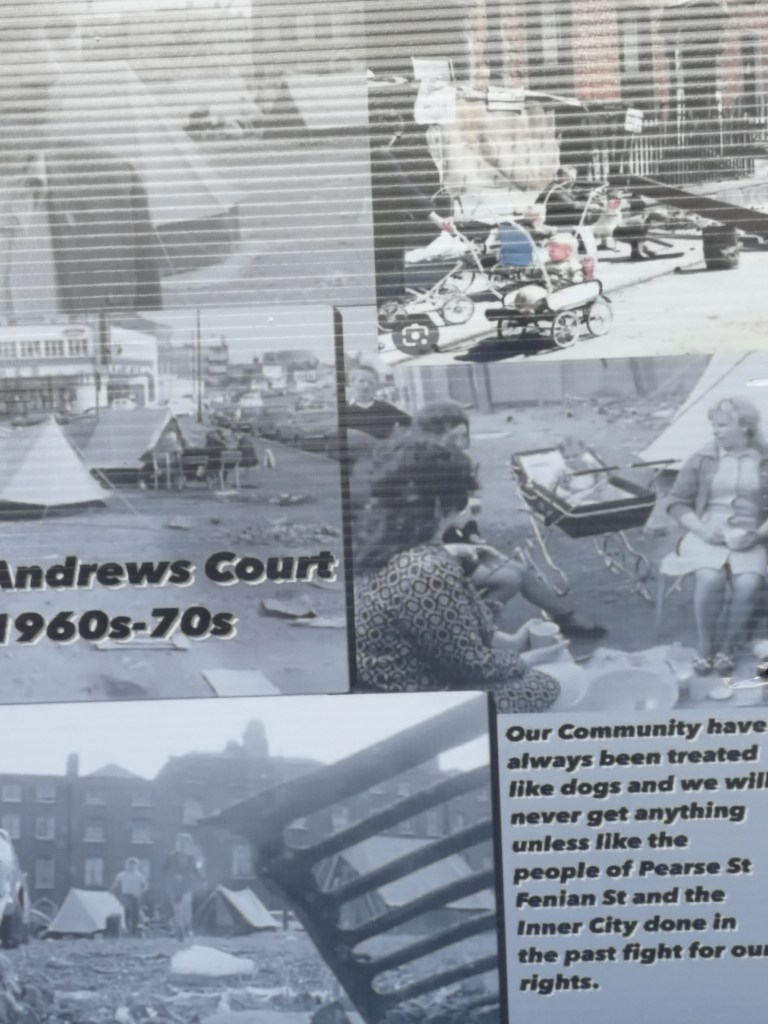

HISTORY of struggle … and of neglect

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Dublin had the worst housing in the United Kingdom and many of its elected municipal representatives – including a number of Nationalists of Redmond’s party – were themselves slum landlords.

When the Irish Transport and General Workers Union was formed by Jim Larkin with assistance from James Connolly and the Irish Women Workers’ Union founded by Delia Larkin, many of the dockers, carters and Bolands Mill workers who joined them came from the south docklands.

And when the employers’ consortium led by William Martin Murphy set out to break the ITGWU in 1913, many of those workers

… Stood by Larkin and told the bossman

We’d fight or die but we would not shirk.

For eight months we fought

And eight months we starved,

We stood by Larkin through thick and thin …4

And the women of Bolands’ Mill were the last to return to work, which they did singing, in February 1914.

They also formed part of the Irish Citizen Army, the first workers’ army in the world,5 to defend the striking and locked-out workers from the attacks of the Dublin Metropolitan Police and which later fought prominently in the 1916 Easter Rising.6

Many also joined the larger Irish Volunteers which later became the IRA, along with Cumann na mBan,7 fighting in the Rising, the War of Independence and the Civil War, supporting resistance of class and nation for decades after.

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (the Fenians) was founded in the area; Peadar Macken8 was from here and has a street named after him; Elizabeth O’Farrell9 is from the area too with a small park named after her and Constance Markievicz10 also lived locally.

The Pearse family lived in the area too and Willie Pearse and his father both worked on monumental sculpture at the same address; Connolly and his family for a while lived in South Lotts.

The working class communities in urban Ireland suffered deprivation throughout the over a century of the existence of the Irish state and the colonial statelet. The communities in dockland suffered no less, traditional work gone, public and private housing in neglect in a post-industrial wasteland.

The population of Ireland remained static from the mid-1800s until the 1990s, despite traditionally large families — emigration in search of employment kept the numbers level. Married couples lived with parents and in-laws while waiting for a house or flat – or emigrated.

In the 1980s, like many parts of the world, Ireland fell prey to what has been described as the “heroin epidemic” and the neglected urban working class worst of all, with the State assigning resources to fight not so much the drug distributors as the anti-drug campaigners.

One of those in the meeting became outwardly emotional when he talked of “the squandered potential” of many people in the local community.

The heirs of these then are the marginalised and abandoned that are targeted with disinformation and manipulated by the far-Right and fascists, to twist their anger and despair not against the causes of their situation but against harmless and vulnerable people.

But the Left has to take a share of the blame, for leaving them there in that situation, for not mobilising them in resistance. After all, issues like housing, education and employment are supposed to be standard concerns for socialists, of both the revolutionary and the reformist varieties.

Republicans cannot avoid the pointing finger either. These communities provided fighters and leaders not only in the early decades of the 20th Century but again from the late 1960s and throughout the 30 years war.

The Republicans led them in fighting for the occupied Six Counties but largely ignored their own economic, social and educational needs at home. Perhaps this is why the people are now organising themselves.

“THEY DON’T VOTE”

A number of the local people to whom I spoke quote a local TD (Teachta Dála, elected representative to the Irish parliament) who commented that most of the local residents don’t vote in elections.

Whether he meant, as some have interpreted, that therefore they don’t matter or, that without voting, they cannot effect change, is uncertain. However, community activism is not necessarily tied to voting in elections.

As we know from our history and that of others around the world, voting is not the only way to bring about change and, arguably, not even the most effective one.

Whatever about that question, people are getting organised in these communities and those who hold the power may find that they are in for a fight.

End.

FOOTNOTES

1From song by Pet St. John, Dublin in the Rare Aul’ Times.

4From The Larkin Ballad, about the Lockout and the Rising, by Donagh McDonagh, whose father was one of the fourteen shot by British firing squad after the 1916 Rising.

5Formed in Dublin in 1913 to defend strikers and locked-out workers from the Dublin Metropolitan Police; members were required to be trade union members. The ICA was unique for another reason in its time: it recruited women and some of them were officers, commanding men and women.

6Historian Hugo McGuinness based on the other side of the Liffey believes that the reason the British troops sent to suppress the Rising disembarked at Dún Laoghaire rather than in the Dublin docks was because they feared the landing being opposed by the Irish Citizen Army and its local supporting communities.

7Republican Female military organisation, formed 1914.

8Fenian, socialist, trade unionist, house painter who learned and taught Irish language, joined the Irish Volunteers, fought in the Rising and was tragically shot by one of the Bolands Mill Garrison who went homicidally insane (and was himself shot dead).

9Member of the GPO Garrison in the 1916 Rising, subsequently negotiator of the Surrender in Moore Street/ Parnell Street and courier for the 1916 leadership to other fighting posts.

10Member of multiple nationalist organisations, also ICA and in the command echelon of the Stephens Green/ College of Surgeons Garrison. Also first woman elected to the British Parliament and first female Labour Minister in the world.

SOURCES & FURTHER READING

Biography Peadar Macken: https://www.dib.ie/biography/macken-peter-paul-peadar-a5227