Diarmuid Breatnach

(Reading time: 5 mins.)

Years ago we did not have the USA import of ‘trick or treat’ – but we did have Halloween. In fact, the UStaters got their Halloween originally from – us. Yes, us.

And it was based on the ancient Gaelic feast of Samhain (which is also the name of the month in Irish).

“Happy Halloween” as a wish would seem an oxymoron since it is a feast of the dead or at least for the dead and to propitiate pagan gods. It is recorded in Ireland as far back as the 9th Century, one of the four great feast days of the Gaelic year.

While the festival is often described as Celtic, a number of neolithic passage graves in Ireland and in Britain, predating the arrival of the Celts, are aligned to face sunrise at the time of Samhain.

In the Celtic world it seems to have been a particularly Gaelic festival, being also our name for November, with strong survivals in Ireland, parts of Scotland and Manx, though there are also some echoes of customs in Wales and Brittany.

However, some researchers believe that the word Samhain is related to the month of Samon, in an ancient calendar of the Gauls, the main body of Continental Celts.

No ancient feast of Samhain could have involved pumpkins, unless it was something thought up by a deviant among St. Brendan’s followers when they got to America in the mid-6th Century. Of which there are a number of sound reasons for believing they did.

But no plant we know of came back from that voyage.

Pumpkins of course and many other squashes come from Turtle Island/ America, where they were cultivated by the indigenous people as an important source of food or dried to make containers, utensils and even musical instruments — and they taught the settlers how to cultivate them.

Pumpkin pie is a traditional USA settler culture dish, particularly in the annual Thanksgiving feast, where the arrival of the original English settlers is celebrated along with their survival (thanks to help from the Indigenous, against whom they later committed genocide in gratitude).

Although most people in the US will not be conscious of this aspect of the Thanksgiving celebration there is a pushback against it gathering in the US of late, as there is also in many parts of the world against the celebration of the ‘discovery’ of America for European colonisation by Columbus.

IN DUBLIN, IRELAND

The traditional Irish Halloween cake is the báirín (boyreen) breac, the báirín being Irish for a cake, according to Dineen’s Dictionary and breac meaning piebald or speckled (i.e. from the dried fruit), becoming mispronounced as ‘barmbrack’.

Quite when it became traditional Halloween fare I’m not sure but the basic ingredients would have been available centuries ago – except for the tea, which came from China originally and only became widespread in Ireland through our colonisers in the early 1800s.

Now of course, we’re marbh le tae agus marbh gan é (‘killed by tea but dead without it’) and still pronounce our name for the beverage in Irish as apparently they did in English in Shakespeare’s time. Many cultures call it ‘chai’ from which the English soldiers in India brought back ‘char’.

Anyway, to get back to the báirín breac, it was soaking the dried fruits in tea that gave a yellow tint to the dough when it was baked. We children all looked forward to eating the báirín when we got back home after going from door to door collecting donations of apples or nuts or sweets.

Taste apart, it had a ring hidden in it and, though we had no interest in the prospect of marriage symbolism, we each wanted to be the lucky one to get the slice with the ring. Our Da cut up the slices carefully so we couldn’t tell which had the ring and we had to eat them in sequence.

Earlier on the Halloween evening we had been out in costumes knocking from door to door and of course, other children had knocked on our door too. Many of those would have been known to us but it was surprisingly difficult to identify them, even if only face-painted and without a mask.

It was for us a kind of thrill to knock at a neighbour’s door in costume and be unrecognised. All the houses except a very few welcomed callers at Halloween and kept a supply of fresh fruit, nuts and sweets on hand for the callers.

“Any apples or nuts?” we called as they opened the door or, later “Help the Halloween party?” None of that imported “trick or treat” nonsense!

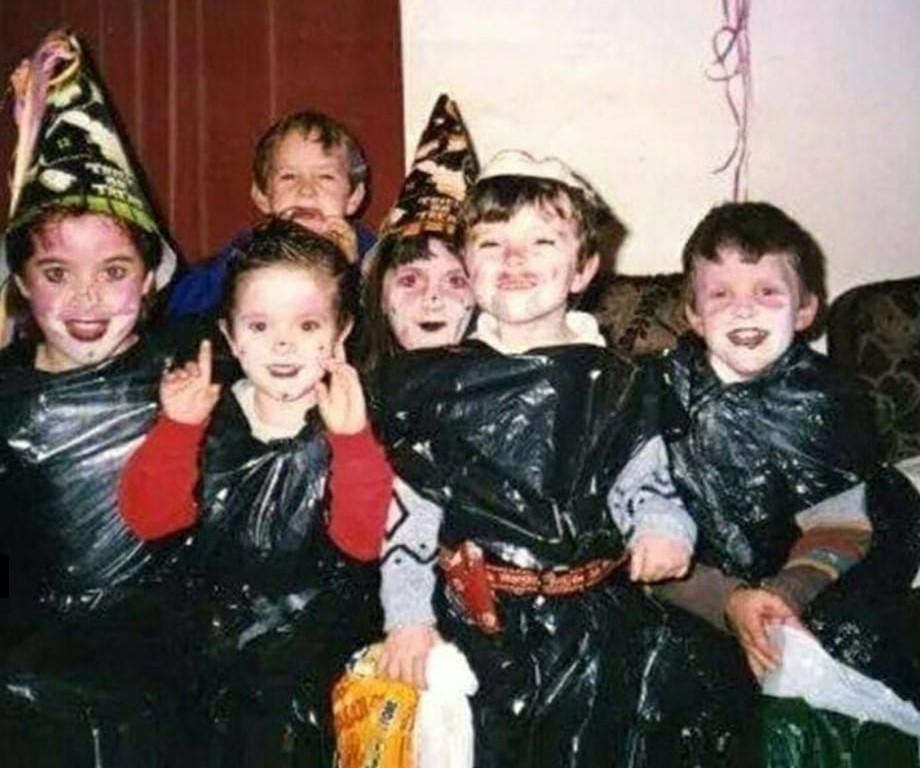

In an amusing piece about that contrast between earlier days and now, a social mores commentator in song at the monthly 1916 Performing Arts Club commented on how pleased he was to see children at his door in costumes made from ‘traditional’ black bin-liners.

Until they spoiled it all by chanting “trick or treat”. “Get outa the garden!” was his response.

You can listen to the song on YouTube here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0k-JmfVZ2lw

Kids still go out (usually escorted by adults now) from door to door at Halloween in Ireland, often with elaborate costumes and chanting the UStater-borrowed “trick or treat”.

In clubs or pubs the festival seems to have been taken over by late teens and young (and not-so-young) adults in costumes depicting horror and death and, for mostly women it must be said, also sexual allure.

And strange though it might seem, the festival was originally primarily for adults and was an occasion of blessing of kine, divination and at least in recorded history, of “mummers” and “guising” going door to door, performing and begging for donations.

‘BARMBRACK’ IN LONDON

In SE London, I was for some years involved in organising an annual Irish Children’s Halloween Party as part of the annual activities of the Lewisham branch of the Irish in Britain Representation Group.

The event was primarily for the benefit of children of the Irish diaspora but children of any other background were welcome to attend.

A local shop selling fresh fruit and vegetables was approached for a donation of fruit and nuts to which they agreed and of course were thanked publicly by word and in print. The local print media were invited to take photos.

The program for the day included street games (but indoors), Halloween activities including apple-bobbing, face-painting and food that would have been traditional for Irish Halloween parties.

Funds raised by the branch through the year bought Irish brand biscuits, Cidona and red lemonade from a shop supplying Irish food items in South London and of course included the ‘barmbrack’.

The children on the day were largely from Irish, Caribbean or mixed background.

As I doled out slices of ‘barmbrack’ to children sitting at the long table, recommending it as traditionally Irish, one Caribbean-seeming child turned to the other and began: “It’s like …” “bun-and-cheese!” finished the other.

This turned out to be a traditional Jamaican food at the other end of the year, at Easter, two slices of a spiced moist ‘brack’ (the “bun”) with a slice of cheese between. They are not as fond of butter in the Caribbean as are the Irish (not many people are) and so that is absent.

One day I decided to try a slice of buttered (of course) ‘barmbrack’ with a slice of cheese on top. The sweetness and slightly spicy taste of the ‘brack’ contrasted with the tart taste of the cheese. And do you know? It’s not at all bad.

End.