Clive Sulish

(Reading time: 4 mins.)

An Irish Republican Easter Rising commemoration conducted on Sunday 20th April followed tradition in some aspects but departed in others. The event in Glasnevin Cemetery was organised by the Anti-Imperialist Action group.

As the 1916 Rising commenced on Easter Monday it is traditionally commemorated on various days around the Easter weekend. The actual date however was 24th April which a now-deceased socialist Republican activist publicly celebrated every year as Republic Day in front of the GPO.1

Among the commemorations organised by Irish Republicans around the past weekend was that by the AIA group on Sunday, rallying by the Phibsboro shopping parade for 1pm, before marching out to Glasnevin cemetry along the Phibsboro Road in two parallel separate lines.

This gathering in the past has been marred by the Special Branch, the political plainclothes police, harassing and attempting to intimidate those present, demanding their names and addresses under anti-terrorist (sic) special legislation. This time they were there but did not approach.2

Just after passing Crossguns Bridge over the Royal Canal, a flare was lit and the march stopped in the street.3

After a short pause the march resumed, led by the colour party,4 six men and women, each carrying a different flag with the Tricolour and Starry Plough in the lead, all dressed in black trousers, white shirts, black berets, sunglasses and lower face masked.

The images of each of the Seven Signatories of the 1916 Proclamation, all shot by British firing squads were on large placards were carried among the marchers: Tom Clarke, James Connolly, Patrick Pearse, Seán Mac Diarmada, Joseph Plunkett, Thomas McDonagh, Eamonn Ceannt.

A variety of flags were also flown among the marchers, including the green and gold Starry Plough,5 Palestinian flag, Basque Ikurrina and red flags (with gold hammer and sickle emblem on at least one).6 The AIA banner carried at the front bore a quotation from Bobby Sands in Irish.

The march soon passed the main gates of Glasnevin Cemetery to their right but continued before turning leftward to then cross over the pedestrian railway bridge to the newer part of Glasnevin Cemetery and up to the monument to the Six armed struggles referred to in the Proclamation.7

Formed in two lines the attendance was welcomed in Irish and English by the event’s MC, calling also for the reading of the Proclamation of Independence, which a man stepped forward to do. The MC recommended a careful reading of the still-relevant document to attendees from abroad.

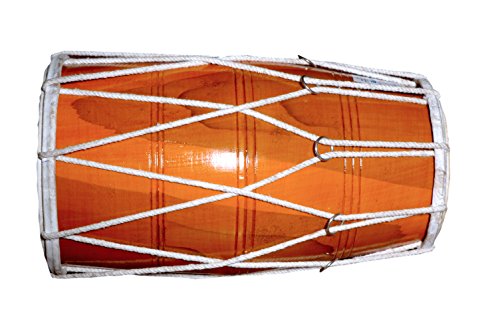

Following the reading, the MC commented on the important role of culture in the 1916 Rising8and called on an activist who he said has done much to promote traditional and folk Irish song, who proceed to sing Patrick Galvin’s Where Oh Where Is Our James Connolly? “with some changes”.

Next the call was given for those who wished to lay floral tributes while the colour party lowered their flags in homage to the fallen to commands in Irish, then slowly raised them again before responding to the command in Irish to stand ‘at ease’.

Another activist was called to read the 1915 statement on the Irish Citizen Army by James Connolly in which the revolutionary leader outlined the police violence during the 1913 Lockout that created the need for the ICA and how it had gone beyond defence in assertiveness.

The statement declared its class allegiance and origins “Hitherto the workers of Ireland have fought as parts of the armies led by their masters, never as members of an army officered, trained, and inspired by men of their own class.”

The PA amplification failed on the reader but she carried on in a strong voice reading Connolly’s words that the ICA sought alliance with all progressive forces but remained independent, not to be bound by the limits others set themselves and going further on their own if necessary.9

Another singer was called to perform Erin Go Bragh10 specifically about the 1916 Rising (by Dominic Behan, originally called A Row in the Town).

It is traditional for organisations to deliver a keynote message or statement of aims at 1916 commemorations and a statement was read on behalf of the Irish Socialist Republican Movement (of which the AIA is a part) restating the objectives of national independence and socialism.

In that context the struggles against the Irish ruling class putting the State into imperialist alliance and against the British occupation of the nation, also a NATO member, were greatly important and the Gardaí had broken a comrade’s foot in that struggle.

Referring to the international context of the 1916 Rising and the international connections of the revolutionary movement in 1916, the MC read out a fraternal message to AIA from the People’s Front for the Liberation of Palestine,11 declaring that the struggles of both peoples are one.

The event concluded at around 2.45pm with a singer performing Amhrán na bhFiann12 (first verse and chorus) followed by an announcement or reminder of a public meeting organised by the AIA titled Rebuilding the Republic to take place at 4pm at a venue not very far distant.

End.

Footnotes

1Easter is a religious festival and its date varies from year to year according to computations based on the lunar and solar calendars and cannot fall on the same date annually in the Gregorian calendar (or the Julian one). After the insurrectionary forces had taken possession of the building, Patrick Pearse with James Connolly by his side read the Proclamation outside the General Post Office (GPO) building on the first day of the Rising (after its rescheduling from the previous day, Sunday): 24 April 1916. Tom Stokes tried for years to have the date adopted as Republic Day and annually organised an event outside the GPO on that date. After his death others carried on commemorating the date but rather than outside the GPO, at Arbour Hill. The Republican movement continues to hold its 1916 commemoration events over the Easter weekend.

2Possibly because the dust has not yet settled on the Gardaí’s recent violent arrests on 23 peaceful activists in three different events over four days (See Rebel Breeze’s Irish State Ramps Up Repression) recently.

3This spot has a 1916 history: A group of Irish Volunteers walked from Maynooth on Easter Monday along the banks of the Royal Canal, meeting two Irish Volunteers guarding the bridge and that night slept in Glasnevin Cemetery. The following morning they continued their journey to the city centre. Later, as the Rising was being suppressed, the British soldiers placed a barrier on the Bridge and prevented most people from passing through. A local man who had been deaf from birth failed to heed the soldiers’ challenge and they shot him dead.

4The ‘colour party’ carries the ‘colours’, i.e the flags and usually marches at the front. The number and type of flags varies but Irish Republican colour parties always carry the Tricolour among them, usually followed by the Starry Plough of which for many years the white stars on a blue background version was the most common. Often a flag of each of the four provinces would also carried and the Gal Gréine (or Sunburst) of the Fianna and of the Fenians would be carried too. The Harp on a Green background was another flag that was often carried by Colour Parties.

5The original design of the flag of the first workers’ army in the world, the Irish Citizen Army, created in 1914. It is a plough following the form of the Ursa Mayor constellation with a sword replacing the ploughshare.

6This is usually considered a symbol inherited from the Bolsheviks, the sickle representing the agricultural workers and the hammer, the industrial workers, their conjunction symbolising unity of peasants and industrial proletariat.

71798 and 1803 (United Irishmen), 1848 (Young Irelanders), 1867 (Fenians), 1882 (Invincibles group within the Fenians), 1916 (IRB, Irish Volunteers, Irish Citizen Army, Cumann na mBan, Fianna Éireann)

8Irish language revival, national theatre groups, national sports, poetry, music and song all contributed to an atmosphere conducive to resistance and uprising.

9However it may be for others, for us of the Citizen Army there is but one ideal – an Ireland ruled, and owned, by Irish men and women, sovereign and independent from the centre to the sea, and flying its own flag outward over all the oceans. We cannot be swerved from our course by honeyed words, lulled into carelessness by freedom to parade and strut in uniforms, nor betrayed by high-sounding phrases.

The Irish Citizen Army will only co-operate in a forward movement. The moment that forward movement ceases it reserves to itself the right to step out of the alignment, and advance by itself if needs be, in an effort to plant the banner of freedom one reach further towards its goal. https://www.marxists.org/archive/connolly/1915/10/forca.htm

10The slogan Éirinn (or Éire) go brách (“Ireland for ever”) was rendered in English spelling as Erin go bragh.

11 A socialist and secular resistance Palestinian resistance organisation; its armed wing is Brigades of the Martyr Abu Ali Mustafa which has been part of the armed resistance throughout the period, often in coordination with other groups.

12In a reversal of the usual sequence, the lyrics of this song by Peadar Kearney and Patrick Heeney were first composed in English but later translated to Irish, that being the most popular version of the chorus today.

Further information