Clive Sulish

(Reading time: 7 mins.)

Large numbers attending a rally Sunday afternoon were addressed by a number of speakers from a platform in the centre of the 1916 Terrace organised by the Moore Street Preservation Trust on part of the very site they wished to preserve.

Fintan Warfield, a Sinn Féin Senator (and cousin of Derek and Brian Warfield of the Wolfe Tones) came on stage to perform Come Out Yez Black ‘n Tans followed by Grace, about Grace Gifford’s wedding to Vol. Joseph Plunkett hours before his execution by British firing squad.

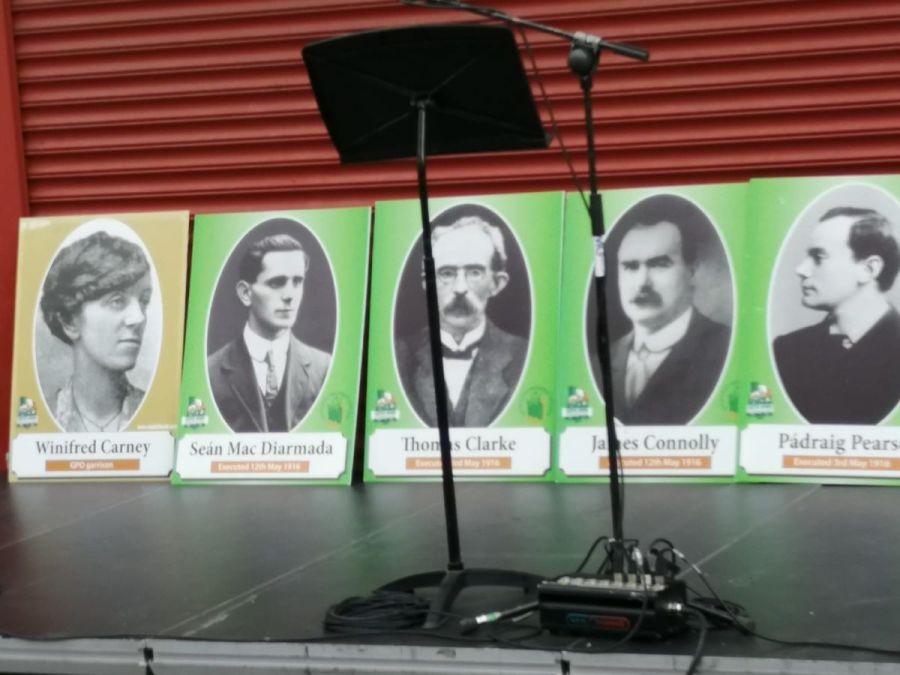

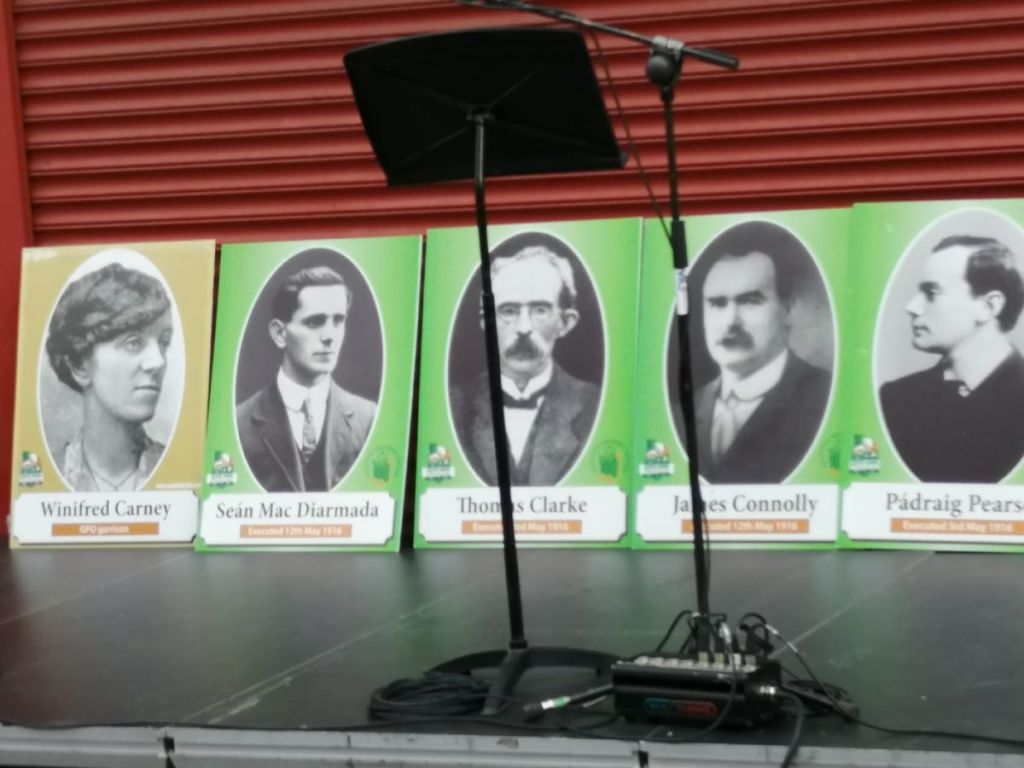

Warfield performed in front of a number of large board posters bearing the images of a number of leaders of the 1916 Rising who had occupied Moore Street in 1916 and Vols. Elizabeth O’Farrell and Winifred Carney, two of the three women Volunteers who had been part of the garrison.

The start of the rally however was delayed, apparently awaiting the arrival of Mary Lou Mac Donald, billed as the principal speaker on the Moore Street Preservation Trust’s pre-rally publicity.

Eventually Mícheál Mac Donncha, Secretary of the Trust and a Sinn Féin Dublin City councillor came on the stage to promote some MSPT merchandise (some of it for free) and to introduce the MC for the event, Christina McLoughlin, a relative of Comdt. Seán McLoughlin.

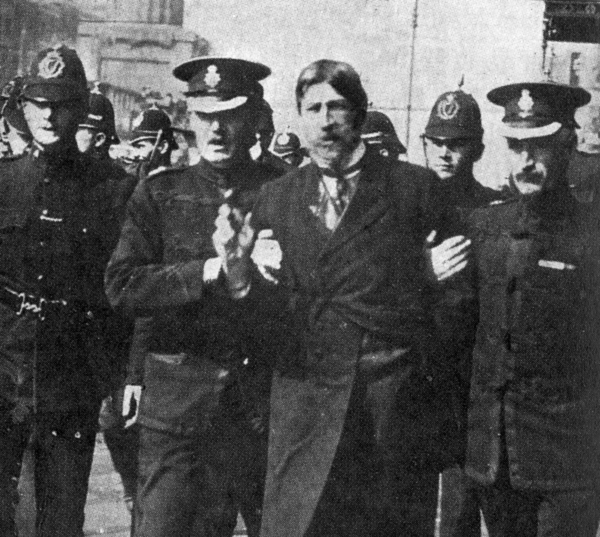

Vol. Seán McLoughlin had been appointed Dublin Commandant General by James Connolly during the GPO evacuation and was about to lead a charge on the British Army barricade in Parnell Street when the decision was taken to cancel after which he organised the surrender.

He later became a communist and was never acknowledged at Commandant level by the War Pensions Dept. of the State under De Valera, despite his rank in Moore Street and later also in the Civil War in Cork.

Sean’s relative Christina McLoughlin welcomed Mary Lou Mac Donald on to the stage.

Mac Donald’s appearance on the stage received strong applause. In fairness, many present, if not most, were of the party faithful. Despite the presence of some younger people, the general age profile was decidedly from the 40s upwards, indeed many being clearly in the later third.

Mac Donald, who is not an Irish speaker, read the beginning of the address well in Irish before going on to talk in English about the importance of Moore Street site in the history of the 1916 Rising and in Irish history generally and how her party in government would save it.

After the applause for Mac Donald, the MC called Proinnsias Ó Rathaille, a relative of Vol. Michael The O’Rahilly, who was mortally wounded leading a charge up Moore Street against a British Army barricade in Parnell Street and who died in the nearby lane that now bears his name.

Ó Rathaille’s address was heavy in the promotion of the Sinn Féin party and, in truth rather wandering so that he had to return to the microphone after he’d concluded, to announce Evelyn Campell to perform a song she had composed: The O’Rahilly Parade (the lane where he died).

Campell is a singer-songwriter and has performed in Moore Street on previous occasions, the first being at the invitation of the Save Moore Street From Demolition group who were the only group to campaign to have the O’Rahilly monument finally signposted by Dublin City Council.

McLoughlin announced Deputy Mayor Donna Cooney to speak, a relative of Vol. Elizabeth O’Farrell, one of the three women who were part of the insurrectionary forces occupying Moore Street. Cooney is a Green Party Councillor and a long-standing campaigner for the conservation of Moore Street.

While speaking about the importance of Moore Street conservation for its history and street market, Cooney also alluded to its deserving UNESCO World Heritage status, adding that the approval of the Hammerson plan for the street was in violation of actual planning regulations.

Next to speak was Diarmuid Breatnach, also a long-time campaigner, representing the Save Moore Street From Demolition campaign group which, as he pointed out has been on the street every Saturday for over a ten years and is independent of any political party or organisation.

Breatnach also raised the UNESCO world heritage importance, as the SMSFD group were first to point out and have been doing for some years, based on a number of historical “firsts” in world history, including the 1916 Rising having been the first anti-colonial uprising of that century.

The Rising was also the first ever against world war, Breatnach said. He told his audience that the Irish State has applied for UNESCO heritage status for Dublin City, but only because of its Victorian architecture and that it had once been considered “the second city of the British Empire”.

Stephen Troy, a traditional family butcher on the street, was next to speak. He described the no-notice-for-termination arrangements which many phone shops in the street had from their landlord and how Dublin City Planning Department had ignored the many sub-divisions of those shops.

Troy’s speech was probably the longest of all as he covered official attempts to bribe the street traders to vote in favour of the Hammerson plan and what he alleged was the subversion of the Moore Street Advisory Group which had been set up by the Minister for Heritage.

It began to rain as Troy was drawing to a close but fortunately did not last long.

Jim Connolly Heron, a descendant of James Connolly and also a long-time campaigner for Moore Street preservation was then called. Speaking on behalf of the Trust, Connolly began by reading out a list of people who had supported the conservation but had died along the way.

Connolly Heron went on to promote the Trust’s Plan for the street which had been promoted by a number of speakers and to announce the intention of the Trust to take a case to the High Court for a review of the process of An Bord Pleanála’s rejection of appeals against planning permission.

The MC acknowledged the presence in the crowd of SF Councillor Janice Boylan, with relatives among the street traders and standing for election as TD and Clare Daly, also standing for election but as an Independent TD in the Dublin Central electoral area.

MOORE STREET, PAST AND PRESENT

Moore Street is older than O’Connell Street and the market is the oldest open-air street market in Ireland (perhaps in Europe). It became a battleground in 1916 as the GPO Garrison occupied a 16-house terrace in the street after evacuating the burning General Post Office.

At one time there were around 70 street stalls in the Moore Street area selling fresh fruit, vegetables and fish and there were always butchers’ shops there too. But clothes, shoes, furniture, crockery and vinyl discs were sold there too, among pubs, bakeries and cafés.

Dublin City Planning Department permitted the development of the ILAC shopping centre on the western side of the street centre and the Lidl supermarket at the north-east end of the street, along with a Dealz as the ILAC extended to take over the space on its eastern side.

While many Irish families turned to supermarkets, people with backgrounds in other countries kept the remaining street traders in business; but the property speculators ran down the street in terms of closing down restaurants and neglecting the upkeep of buildings.

The authorities seem to have colluded in this as antisocial behaviour that would not be tolerated for a minute in nearby Henry Street is frequently seen in Moore Street.

The new craft and hot food stalls Monday-Saturday run counter to this but are managed by the private Temple Bar company which can pull out in a minute. On Sunday, the street is empty of stalls and hot food or drinks are only available in places that are part of the ILAC shopping centre.

The O’Reilly plan was for a giant ‘shopping mall’ extending to O’Connell Street and was paralysed by an objectors’ occupation of a week followed by a six-week blockade of the site, after which a High Court judgment in 2016 declared the whole area to be a National Historical Monument.

A judge’s power to make such a determination was successfully challenged by then-Minister of Heritage Heather Humphries in February of 2017. NAMA permitted O’Reilly to transfer his assets to Hammerson who abandoned the ‘shopping mall’ plan as not profitable enough.

The Hammerson plan, approved by DCC and by ABP is for a shopping district no doubt of chain stores like Henry Street or Grafton Street, also an hotel and a number of new streets, including one cutting through the 1916 central terrace out to O’Connell Street from the ILAC.

In the past dramatist Frank Allen organised human chains in at least three ‘Arms Around Moore Street’ events and the Save Moore Street 2016 coalition organised demonstrations, re-enactments, pickets and mock funerals of Irish history (i.e under Minister Humphries).

The preservation campaigning bodies still remaining in the field are the SF-backed Moore St. Preservation Trust and the independent Save Moore St. From Demolition group. The former is only a couple of years in existence and the latter longer than ten years.

However, both groups contain individuals who have been campaigning for years before that. The MSPT tends to hold large events sporadically; the SMSFD group has a campaign stall on the street every Saturday from 11.30am-1.30pm. Both have social media pages.

LEGISLATION & COURT CASES

2007 Nos. 14-17 Moore Street declared a National Historical Monument (but still owned by property developer Joe O’Reilly of Chartered Land)

2015 Darragh O’Brian TD (FF) – Bill Moore Street Area Development and Renewal Bill – Passed First Reading but failed Second in Seanad on 10th June 2015 by 22 votes against 16.

2015 – Colm Moore application — 18th March 2016: High Court judgement that the whole of the Moore Street area is a national historical monument.

2017 – February – Minister of Heritage application to Court of Appeal – judgement that High Court Judge cannot decide what is a national monument.

2021 — Aengus Ó Snodaigh TD (SF) – 1916 Cultural Quarter Bill – reached 3rd Stage of process; Government did not timetable its progress to Committee Stage and therefore no progress.

2024 – Property Developer Hammerson application to High Court Vs. Dublin City Council in objection to decision of elected Councillors that five buildings in the Moore Street area should receive Protected Structure status as of National Historical Heritage. Hammerson states that the decision is interfering with their Planning Permission. Case awaits hearing.

POSTSCRIPT

Someone commented later that in general the rally, from the content of most of the speeches, had been at least as much (if not more) of a Sinn Féin election rally as one for the conservation of Moore Street.

That should have been no surprise to anyone who knows that any position taken by Sinn Féin activists tends to be for the party first, second and third. And with the Irish general elections only weeks away, well …

And while Mac Donald spoke in Dublin of the importance of Ireland’s insurrectionary history and the need to conserve such sites, her second-in-command Michelle O’Neil was laying a wreath in Belfast in commemoration of the British who were killed in the First imperialist World War.

End.