Diarmuid Breatnach

(Reading time: 3 mins.)

Dublin Political History Tours Facebook page reminds us of the 20th September anniversary of the public execution on of “Bold Robert Emmet, the darling of Erin”, leader of the unsuccessful Republican insurrection in Dublin on 23rd July 1803.

I reproduce the Dublin Political History Tours text (reformatted for R. Breeze):

On Saturday we passed by the anniversary of the execution by the English occupation forces of Robert Emmet, United Irishman. Emmet had been condemned to death for planning an insurrection for Irish self-determination which the English Occupation called ‘treason’.

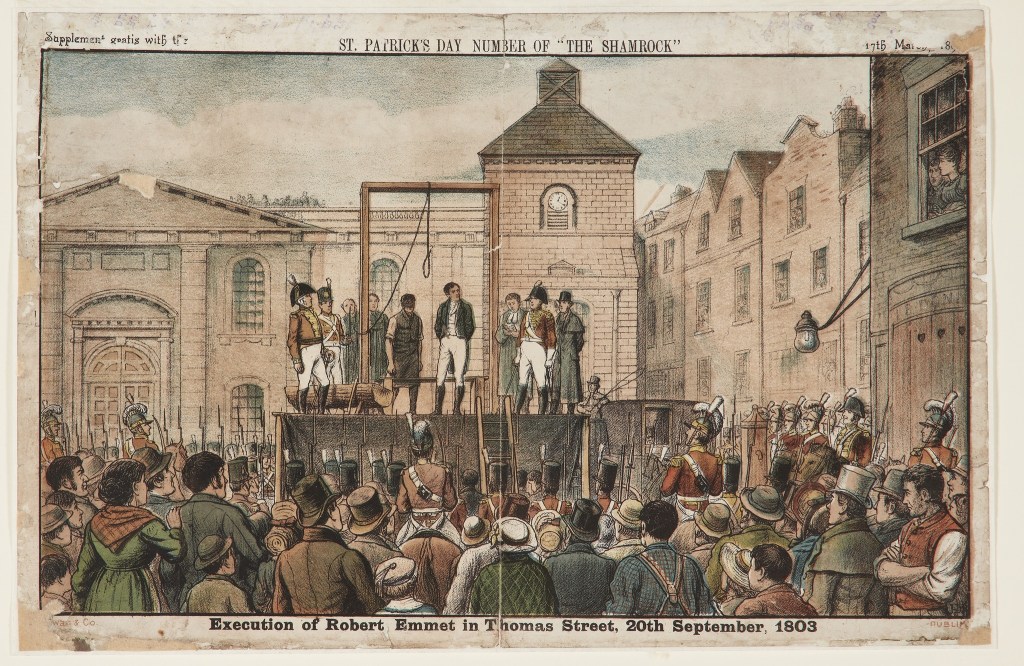

Leaving behind in Kilmainham Gaol his comrade Anne Devlin, who had endured torture and death of family members without giving the authorities any information, Emmet was taken to the front of St. Catherine’s Church.2

(This building is) on Thomas Street in Dublin’s Liberties area on the west side of the city centre. The site chosen was sending a message to the populace of the area that had nationalist and republican sympathies.

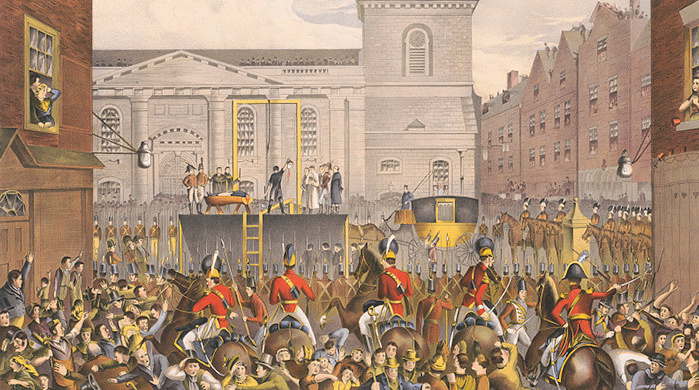

There, in front of a huge crowd and many soldiers, Emmet was hanged and then beheaded, the executioner holding up the dripping head to the crowd. His body was later returned to the Gaol before being later buried in Bully’s Acres in the grounds of the Royal Hospital Kilmainham.

Emmet’s corpse was later disinterred in secret and reburied elsewhere by friends or family and, despite a number of sites being speculated, its current location is unknown.

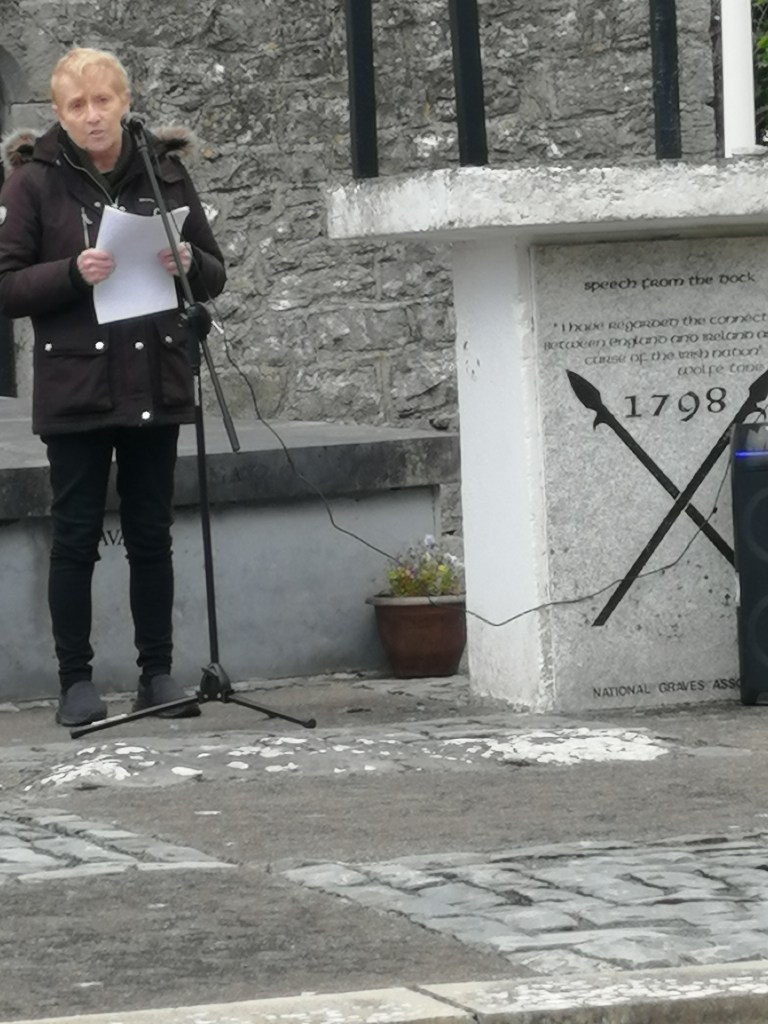

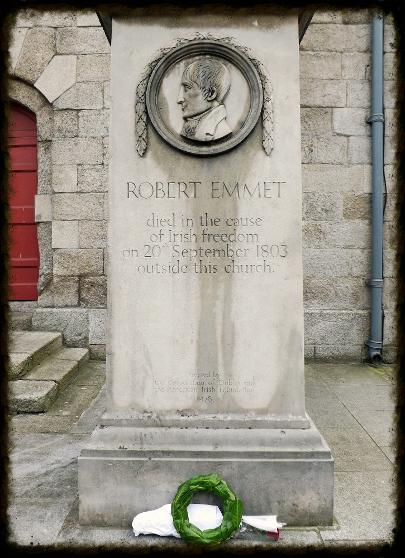

There is a monument to the execution inside the grounds of the St. Catherine’s building and a stone plaque on the wall outside it.

Robert Emmet was very popular in Ireland at the time and his memory is still. A statue in his honour stands in Dublin’s Stephens Green, a replica of another two at locations in the United States.

Anne Devlin endured three years in Kilmainham Gaol and according to Richard Madden (1798 – 5 February 1886), chronicler of the United Irishmen who sought her out, was followed everywhere in public by police.

(who were) observing anyone who she spoke to, as a result of which many were afraid to speak to her. Her body lies in Glasnevin Cemetery.

“Bold Robert Emmet” is a traditional ballad in the martyr’s honour and “Anne Devlin” also has a much more recent song in hers by Pete St.John.

(quoted passages end)

In the 1916 Proclamation of Independence, “the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland” is proclaimed and that “six times in the past 300 years they have asserted it in arms”, probably referring to insurrections of 1641, 1689, 1798, 1803, 1848 and 1867.3

Historians have mostly dismissed the 1803 uprising as never likely to succeed but a minority have rated the preparations highly, including the innovations of signal rockets and folding pike handle for concealed personal carrying.

RH Madden, the first historian of the United Irishmen was of the opinion that the insurrection attempt was engineered by the English Occupation’s administration in Dublin Castle in order to justify continued repression of Irish republicanism and to eliminate some leaders.

Generally historians have tended not to give much credence to Madden on that issue but it is certain that the Occupation had a network of spies in operation in Ireland and that some had penetrated Emmet’s conspiracy.

However it is not for the manner of the 1803 insurrection that Emmett has been fondly remembered in Ireland to this day 123 years later – and abroad for decades after his death4 – but for the calm manner in which he faced his enemies, including his executioner and for his eloquence at his trial.

Past insurrections contain lessons for us today and a serious evaluation should be attempted, perhaps with a number of submissions from historians of different opinions on the matter, to deal with questions around Emmet’s return from France and the planning of the insurrection in Ireland,.

For us today however, whether Republicans or more generally anti-colonialists and anti-imperialists, it is also necessary to revere the memory of revolutionary action for a democratic Irish Republican and to uphold his and Anne Devlin’s spirit of defiance in resistance.

End.

Note: If you found this article of interest, why not register with Rebel Breeze for free, so that you will be notified by email of subsequent articles. You can de-register any time you wish.

FOOTNOTES

1From Emmet’s famous speech from the dock of the courthouse in Green Street that not until then should his epitaph be written. I have no doubt that Emmet meant “nation-states of the world” because Ireland was in his time more than what we would understand today from the vague term of “country” – it was clearly, though under foreign occupation, already a nation with its own unique culture and a long history. She has yet to take that place to which Emmet referred and aspired for her.

2Note that was the Anglican St. Catherine’s Church, as a Catholic St. Catherine’s is also located not far away on Meath St. The Anglican church was closed in the 1960s but later reopened and reconsecrated as an Anglican Church. The interior seems very untypical of Anglican churches. Emmet was raised in the Anglican faith.

3Believed to refer to, in sequence: the Irish and Norman Irish clans in the Confederation’s uprising, the Williamite War’s, United Irishmen’s, Robert Emmets’, Young Irelanders’, the Fenians’. Coincidentally, the large monument to uprisings in Ireland erected by the National Graves Association in the St. Paul’s section of Glasnevin Cemetery also includes only six dates but they are of Republican risings only, beginning with 1798 and ending with 1916.

4I read somewhere that even in England Radicals would read Emmet’s speech as a high point of their events including formal dinners.

SOURCES