Diarmuid Breatnach

They came down O’Connell Street in their tens of thousands – colourful banners and heart-shaped balloons, music in sections, black, brown and white faces and if many were old, many were also young – and not just the children brought by a parent. “Right to life” was the most common chant, obviously tailored to undermine their opposition’s “Right to choose”, from those who favour the unfettered right to abortion. And LIFE is the name of the organisation that brought these marchers together on their annual march through Dublin city centre.

“Nobody has a right to kill!” was the last line in another chant. So with that, the name of their organisation and “Right to life”, we have what they are about, right? They are for life and are upholding, apparently, the Christian Commandment “Thou shalt not kill”. Yes, it was there on the tablets of stone Moses brought down the mountain, Number Six – wayyy down the list. Actually, apparently in Hebrew it translates as “Though shalt not murder”. And defining “murder” is not so simple either. But anyway, the Jewish faith has the same prohibition. In fact, there is hardly a religion that does not. Of course, the Old Testament also calls for “an eye for an eye” and says that “you shall not suffer a witch to live”. But anyway ….

Interestingly, the highest leaders of organised religions across the world have blessed their soldiers as they went off to kill soldiers and civilians in other lands. Sometimes their victims were infidels according to the ones who were killing them but often they didn’t even have that excuse, as when the first Crusade attacked the overwhelmingly Christian city of Damascus, or when Catholic Spain fought Catholic France, or when Protestant England fought Protestant Germany, or Catholic Italy invaded Catholic Spain, Catalonia and the Basque Country. But presumably, those pastors, bishops, pontiffs, cardinals and mullahs can fall back on the dispute about the meaning – it wasn’t “murder”, it was legal killing.

The wiping out of the Guanches of the Canaries was not murder, the genocide of the indigenous American “Indians”, the enslavement and consequent killing of hundreds of thousands of Africans – they were not murder either. Nor the wiping out of every single Tasmanian and most of the Australian Aborigines. The West was exploring and, by the way, bringing Christianity and civilization to those poor benighted people.

I’d hazard a guess that compiling a list of Christian bishops in most denominations who condemned the wars in Malaya, Korea and Vietnam would a short one. Cardinal Spellman, notorious as anti-communist and anti-militant organized labour, a supporter of McCarthy’s witch-hunts, had the words “Kill a Commie for Christ” put into his mouth due to his enthusiastic support for the US waging the Vietnam War. Leaving out the maimed in mind and body, even in the wombs of their mothers, somewhere between 1.5 and 3.6 million were killed in that war – but presumably they weren’t murdered.

Billions of people are killed by unsafe working conditions, uncontrolled pollution, police and army repression, crime in slums, famine, alcohol and drug addiction, curable disease – almost all conditions that can be avoided except that doing so would cut into profits of local capitalists and/or foreign “multinationals” (read, monopoly capitalists/ imperialists). Those “entrepreneurs” aren’t murdering anyone either, even when their practices are illegal (even by their own laws) …. The ways of God are indeed mysterious, certainly so if the ways of his representatives on Earth are anything to go by.

I have digressed, mea culpa. I have gone down a well-worn philosophical and logical path to ask a particular question: Are those tens of thousands marching down O’Connell Street really for Life and against killing human beings? I doubt it and I have not seen among their number most people I see against the bombardment of Gaza or the invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan, nor vice versa. A few, certainly, but not many. So I have to assume that it is not life that they value so much, except the life of a foetus. And once born, it is pretty much up to luck what happens to that foetus, as far as most of these ardent defenders of life are concerned.

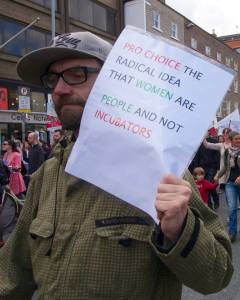

As I said, that philosophical and logical path of discussion has been well trodden before me and no doubt to better effect than mine here. But I wish now to take another path of discussion – I wish now not to criticise the opposition, the anti-abortion brigade, but rather ours, the pro-choice movement of which loosely I am a member.

All Irish surveys and opinion polls published show a rising trend of support for the unfettered right to abortion, even if that section is still a minority. The majority of those polled have been for a greater access to abortion than is currently available in this state. Furthermore, some scandals involving refused abortions, refused permission to travel and the death of a woman who needed an abortion have mobilised considerable passion which the pro-choice movement could enlist in its favour.

Yet, despite what the polls tell us, and despite those high-profile cases, the anti-abortioners succeed in mobilising much larger numbers in opposition to abortion than do those who are in favour of permitting it. Putting this conundrum to some pro-choice campaigners, they have all answered to the effect that the anti-abortioners receive huge funding from reactionary political and religious foundations, especially in the USA. They spend millions on advertising and propaganda, I am told.

I’m sorry, I don’t accept that reply. Because despite their well-funded advertising and propaganda, the opinion polls show a climbing majority for some access to abortion and a climbing minority in favour of unfettered access.

The Antis just seem to be better at mobilising their supporters – why is that? Well, the funding again, I’m told. They hire coaches and bus people in. So why can’t we do that? Are we incapable of raising money to hire coaches? Obviously not in the case of the Water Tax, for example. Republican groups hire coaches traveling to other parts of the country and pay their share as individuals; they often fund their posters, placards, banners public meeting-room hires, for example through fund-raising events. We don’t see many fund-raising events in support of the right to abortion. In fact, the public doesn’t see much evidence of the movement as a rule except when we come out to protest about a high-profile case or to oppose the march of the anti-abortioners. And our movement doesn’t seem to do much mobilising for the latter, either. And this march happens every year so it can easily be planned for.

Yet how many were there to show their opposition to these tens of thousands of anti-abortion campaigners? Maybe six hundred …. at a very long stretch, a thousand. Going by the opinion polls, in Dublin alone there are a great many more people who support unfettered access to abortion than appear on that counter-demonstration.

Nor did we even distribute our meagre forces in the most effective way.

Each year, it is the same. The anti-abortion people march down from the Garden of Remembrance, and the pro-choice people wait for them at the Spire. Most on the island, some on the east side pavement. The heaviest concentration of people is on the island (or pedestrian reservation), between the Spire and for about 20 or so yards heading north. Then the line starts to straggle. We didn’t even stretch quite to Larkin’s statue. Even those low numbers, properly distributed, could reach from the Spire down to O’Connell Bridge. But we don’t do that. We bunch up in a short concentration so that every section of their march is quickly past us and, what’s more, it allows them to focus their loudhailers and PA systems on our heaviest concentration in order to drown us out, as they were doing on Saturday.

Broadly speaking, we outnumber them but on most mobilisations, they outnumber us hugely. They appear more broadly militant and organise better. And they learn. I didn’t see anything like as many people in religious robes this year, which suggests to me that they are tailoring their presentation to avoid an over-identification in popular perception with religion. They can’t keep all their religious nutcases under wraps but I saw much less crosses or rosary-waving this year. They have adapted their slogans and chosen what seems the hardest argument to oppose, that which appears to be for “life”, and they ensure that they are all on message, chanting the same lines, again and again.

They are the reactionaries – how is that they seem better able to learn than us? Should it not be the other way around?

End