Diarmuid Breatnach

(Reading time article: 3 mins.)

Earlier this month there was an oration delivered at the grave of Wolfe Tone1 which contained some important elements which deserve inspection and discussion.

– The path to rebuild our struggle is the development of an Anti Imperialist Broad Front – said the speaker. – A United Front of Revolutionary republicans, working in cooperation to advance our common republican objectives and to achieve a common republican programme.

Looking around us at the parties and groups in the socialist and republican spectrum, the ostensibly revolutionary varieties, we see that for many of them, building up their own organisation takes precedence over anything else, including revolution – for them the revolution IS their party.

The call given in this oration runs counter to that kind of thinking. “But we’ve heard all that about ‘unity’ before,” a reader might say. Yes we have and often “unity” meant only “unity” around that particular party or, even more often, around this or that leadership.

There is nothing of that to be found in this address “recognising and respectful of the autonomy and independence of the groups and independents involved”. “Hmmm,” the reader might say “but is it a genuine intention?” Given our experience, it’s a valid and important question.

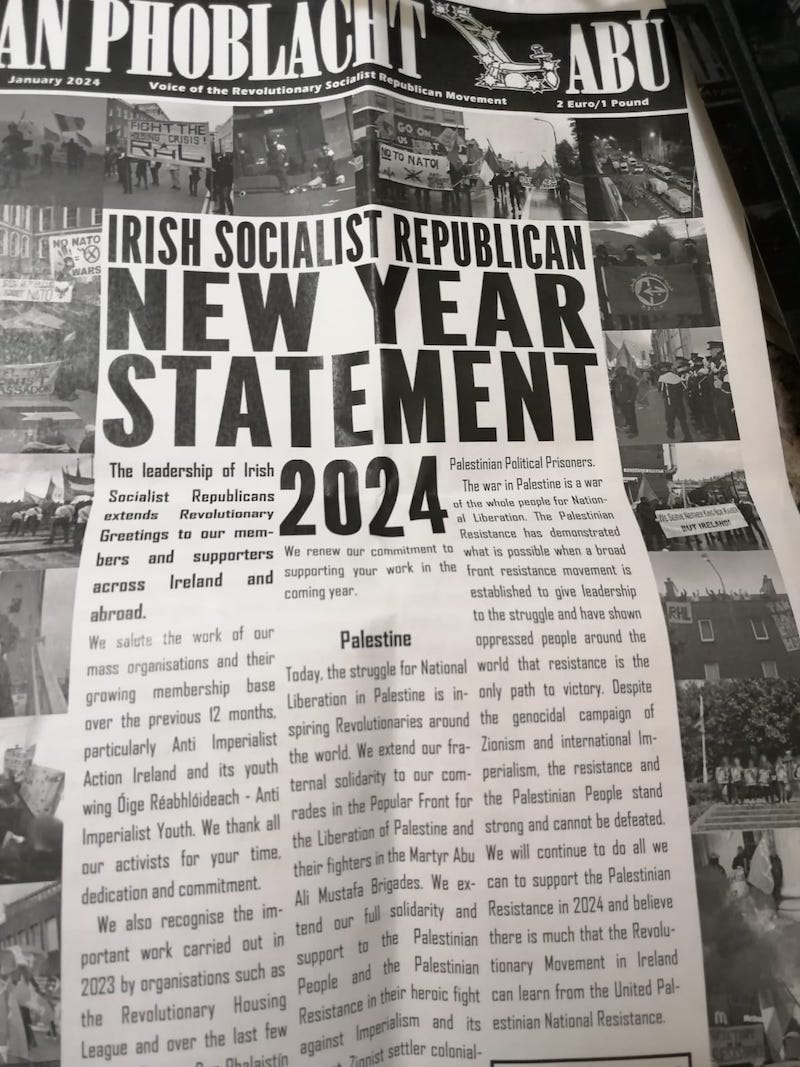

The most dependable test is in the practice. The speaker of the oration at its annual Wolfe Town Commemoration2 was representing the Socialist Republican Movement organisation (more often manifested publicy in recent years in the form of the Anti-Imperialist Action broad group3)

As an independent revolutionary activist for many years I have often participated in AIA’s actions and at times they have supported actions of which I had been part of organising. I have found that their practice matches their words and there is no truer test.

The speaker followed with practical suggestions for the implementation of the broad front: Trust and co-operation must be developed … through activism and the development of National Republican Campaigns that can be taken up by all Republican groups and independents …

There are many campaigns that could be developed from support for POWs to opposing internment and extradition, environmental campaigns such as (overcoming) the unacceptable situation at Lough Neagh, to campaigns that oppose the British and NATO presence in Ireland.

Such a Republican Broad Front would be a fitting tribute to our Patriot Dead, the speaker added, to martyrs like Cathal Brugha,4 who gave his all in fighting for the sovereign, Independent Irish Republic and gave his life on this day in 1922 as a hero in the war in defence of the Republic.

In many of the pleas for unity of the fragmented resistance in Ireland, individuals have called for a conference to form a united front, others called for a unity document of principles around which to unite while in at least one case, two distinct organisations merged.

I have for years spoken out against such endeavours and advocated as a first step unity in practice. If organisations and individuals are not capable of that step, what kind of unity can they achieve around discussion of documents? Unity in practice also helps to break down distrust.

The speaker at the Wolfe Tone commemoration takes the same line, presumably speaking for the SRM when he does so and one supposes that this will continue to be the approach of the AIA in campaigns such as against internment, in solidarity with political prisoners5 or with Palestine.6

The above piece discussed two elements of the oration given by the SRM earlier this month which I believe to be of great revolutionary importance and in need of application in Ireland, one in advocating a principle and the other in suggesting avenues for practical application.

Later I will be taking a look at some other elements in that talk (the text of which, as published by the SRM, I attach as an appendix).

Beirimís bua.

End.

FOOTNOTES

1Wolfe Tone, born into settler stock and of the Establishment Anglican congregation, was a leading figure in the formation of the revolutionary republican organisation The Society of United Irishmen, seeking “to unite Catholic, Protestant (i.e Anglican) and Dissenter” (i.e the other sects, Presbyterian, Methodist, Unitarian, Quaker etc.) to “break the connection with England. In 1798, the year of the Unitedmen uprising, the first of many Irish Republican uprisings and campaigns, Tone was captured by the British Navy on a French warship and, despite his French officer rank, tried and sentenced to death.

Tone died in jail some months before his brother Matthew was taken prisoner during the surrender at Ballinamuck (Baile na Muc) in Co. Longford of another French expedition to Ireland, late and too small, at the tail end of the Rising that year. Also ignoring his officer POW status, he was hanged in Dublin and his body reputedly thrown into the mass grave at Croppies’ Acre in Dublin city.

2Since even earlier than Thomas Davis’ (1814-1845) song In Bodenstown Churchyard, Irish Republican organisations and individuals have been making the pilgrimage to that grave in County Meath, at times with thousands in attendance.

3Also for an intense time as the Revolutionary Housing League in its attempt to spark a movement of occupation of empty properties to overcome the widely-acknowledged housing crisis in Ireland.

4Cathal Brugha (nee Burgess), son of a mixed Catholic-Protestant marriage, was a leading figure in Irish nationalist movement and in Republican rebellion in the last decades of the 19th and early decades of the 20th Centuries, learned Irish as a member of the Gaelic League, member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (which he later left, considering it undemocratic), officer in the Irish Volunteer, 2nd in command in the South Dublin Union in 1916 served as Minister for Defence in the revolutionary government from 1919 to 1922, Ceann Comhairle of Dáil Éireann in January 1919 and its first president from January 1to April 1919, Chief of Staff of the IRAfrom 1917 to 1918. He served as a TD (electe parliamentary representative) from 1918 to 1922. He was mortally wounded by Irish Government troops in the early days of the Irish Civil War.

5Both on their own and for example in support of the Ireland Anti-Internment Campaign.

6Both on their own and for example as part of the Saoirse Don Phalaistín broad front.

APPENDIX

The following is the text of the main oration of which some sections are discussed in the preceding article and more to be discussed anon. It was delivered at the annual Wolfe Tone Commemoration at Bodenstown, organised by the Revolutionary Irish Socialist Republican Movement on Sunday July 7, 2024 and published on its Telegram page.

A Chairde is a chomrádaithe,

Táimid anseo i relig bodenstown ag uaimh ár n-athair, Wolfe Tone agus táimid ag rá go bhfuil an gluaisteacht a bhunaigh sé fós beo, agus tá sé ag fás arís.

Wolfe Tone is the father of Irish Republicanism. We come here each year not just for commemoration, but like Pearse, Connolly, Mellows and Costello before us, we come because we believe that the ideas and the vision that Tone put forward of a free independent Ireland is as relevant today as they were in the 1790s and because we believe that by remaining true to the teachings of Wolfe Tone we can build a revolutionary movement that will successfully free our country. Maybe not today, but our freedom is inevitable.

Tone’s most important belief was that we must ‘break the connection with England’ by any means necessary. It is for this reason that he established revolutionary military-political organisation the United Irishmen in 1791 and led a mass armed uprising in 1798 against British Rule in Ireland.

Tone was also clear that the revolutionary struggle could only be successful if it was based on the masses of the Irish People, stating that, ‘Our Strength shall come from that great and respectable class, the men of no property’.

And in these two simple quotes from Wolfe Tone, we have two of the most important teachings for the Revolutionary Republican Movement today. Firstly, that Republicans must work as a priority for National Liberation by any means we decide necessary.

That we must break the connection with England and defeat all forms of Imperialism in Ireland to establish a sovereign, Independent, Irish Republic.

And secondly, we learn from Tone that the fight for our Republic is a class struggle and that the driving force of that struggle will be the working class fighting for their own liberation.

These are two key teachings that when deviated from lead to compromise and the selling out of our revolution.

It is the duty of all of us here today and of all Republicans across Ireland, to ensure that the struggle for national liberation is kept at the fore of our revolutionary republican objectives and that we work tirelessly to achieve it and to ensure that our movement remains centred on and driven by the working class.

Some other key points laid down by Tone include that Republicanism is Anti Imperialist and it is Internationalist. Our struggle in Ireland is part of a wider international struggle of oppressed people against occupation, colonialism and imperialism.

Tone understood this when he looked to Revolutionary France to support the 1798 uprising. Today, Republicans must fight our struggle while also supporting Liberation struggles around the world in the belief that every blow struck against imperialism brings our victory closer.

So from Palestine to the Philippines and from India to the Basque Country, and everywhere people take a stand against NATO, the Revolutionary Republican movement must raise our cries in solidarity. The tide of revolution is rising in the world and there is much to be optimistic about.

But as revolutionaries we also have to be realistic. Since the time of Wolfe Tone the tide of revolutionary Republicanism has ebbed and flowed.

After the days of Tone and Emmet and the final defeat of the United Irishmen in 1805, Republicanism was reduced to an ember, spoken about in quiet corners until the birth of Young Ireland and the uprisings of 1848 and 1849 when revolutionaries such as Thomas Davis, Fintan Lalor, James Stephens and John O’Mahony would carry forward the vision of Tone, take up the hard work of rebuilding the Republican Movement and become the spark that would renew the Revolutionary fire, giving birth to Fenianism and the struggle that has carried us until today.

And today, we are 26 years on from the surrender of 1998, a surrender that had a devastating effect on the movement. Later this month it will be 19 years since the Provisionals ended their armed campaign.

These two great betrayals have led to the situation where the movement is fractured and split.

The revolutionary forces, though active, are scattered and there is mistrust between Republicans, whether in different groups or independents across Ireland, and this mistrust and division is exploited by our enemies.

It is a situation that all Republicans want to reverse and one of the revolutionary priorities in this phase of our struggle to overcome.

Comrades, like the revolutionary republicans after the defeat of the United Irishmen and Young Ireland, we find ourselves with the hard and gruelling task of rebuilding and reasserting the revolutionary republican struggle.

And the path to rebuild our struggle is the development of an Anti Imperialist Broad Front. A United Front of Revolutionary republicans, recognising and respectful of the autonomy and independence of the groups and independents involved, working in cooperation to advance our common republican objectives and to achieve a common republican programme. This is what our enemies most fear.

But again, this will not just happen overnight.

Trust and co-operation must be developed and we assert that this will be best achieved through activism and the development of National Republican Campaigns that can be taken up by all Republican groups and independents in a unity of purpose, that shows the real and forgotten strength of the Republican Movement.

There are many campaigns that could be developed from support for POWs to opposing internment and extradition, environmental campaigns such as the unacceptable situation at Lough Neagh, to campaigns that oppose the British and NATO presence in Ireland.

Such a Republican Broad Front would be a fitting tribute to our Patriot Dead, to martyrs like Cathal Brugha, who gave his all in fighting for the sovereign, Independent Irish Republic and gave his life on this day in 1922 as a hero in the war in defence of the Republic.

Over the last seven years we have put down a solid foundation as a movement. We have reasserted Irish Socialist Republicanism as the driving force of Revolution in Ireland.

We have recruited a new generation of republicans not damaged by the 1998 surrender who are now working with more experienced republicans to drive the struggle on.

While we can be happy with these achievements, the Republic needs more from each and every one of us and we all need to ask what we as individuals can do to carry the struggle forward.

Now is the time to move to the next phase of development in our revolutionary struggle, unsurprisingly by taking it back to Tone. Now is the time to strengthen and embed ourselves in the people of no property and to engage in systematic Republican Community work across the country.

In doing so, we would do well to return to Seamus Costello and the oration that he delivered from this spot in 1966, signalling the rise of Socialist Republicanism within the Movement. Costello outlined how it was the duty of all republicans to be active in our community.

How we should be involved in community groups, trade unions, tenants and residents associations, sporting, cultural and educational organisations and how we must take and assert our revolutionary republican position within them.

This is a task for all revolutionary republicans. Look at the groups in your area and see which ones your involvement in would advance the strengthening of Socialist Republicanism in your community.

Where no such groups exist, establish them. Where help is needed reach out to us as we have experienced comrades who excel in this area that would be happy to help in this work.

To conclude the comrades, this is a brief outline of our tasks in the time ahead.

While these plans will be deepened with discussion and debate within the movement, no one should leave this graveyard thinking there is no work for them to do, and the responsibility is on you to come forward and volunteer instead of waiting for others to come and ask you.

Our work is to free Ireland and our people by any means necessary to establish the 32 county All Ireland Socialist Republic, sovereign, independent, Gaelic and free, and we will not be stopped.

Redouble your efforts comrades, onwards to the Republic of 1916.

Beir Bua,

Tiocfaidh Ár Lá